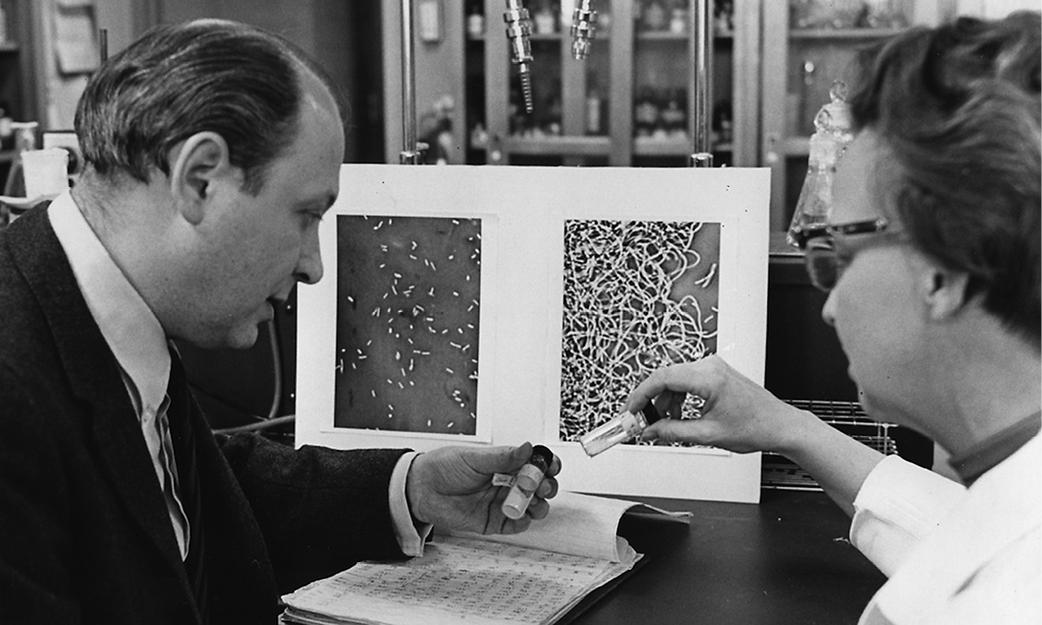

The late Barnett “Barney” Rosenberg used the word serendipity often in recounting the story of cisplatin, the anti-cancer drug first discovered in his Michigan State University research lab in 1965. And it’s a fitting, apt term. How else, after all, might one explain how a biophysicist (Rosenberg), a microbiologist with a medical technology degree from MSU’s School of Veterinary Medicine (Loretta VanCamp) and a graduate student in chemistry (Tom Krigas) could shift from investigating the magnetic fields on the growth of E. coli bacteria to identifying a chemical compound that would successfully help millions battle cancer over the last 40-plus years?

Everything fell into place,” said Krigas, who only landed on Rosenberg’s research team himself after stumbling upon a help wanted ad on a campus bulletin board.

Cisplatin, the name Rosenberg’s team assigned to the chemical compound, has been called the “penicillin of cancer drugs” and remains to many the gold standard to which new cancer medicines are compared. Notably, cisplatin also transformed Michigan State University into a more dynamic research and entrepreneurial enterprise befitting the Spartans Will mindset.

The path to cisplatin

Walking into the lab one day in 1965, Krigas remembers Rosenberg—a scientific researcher who capably toed the line between pragmatism and big dreams—and VanCamp beaming upon verifying that platinum electrodes placed in an E. coli solution could control cell division and the unchecked growth of tumors. Both dreamed about the potential implications for cancer treatment, then a novel scientific field.

“I thought it was a big leap, but they were pretty sure of it,” Krigas said.

Energized but only marginally capitalized, Rosenberg chased external funding to continue experimentation. He secured financial support from platinum companies and scored a spot on a national news program touting the project’s promising results to generate additional interest.

“I remember having dinner at Rosenberg’s house the night that television segment aired, and he answered one phone call after another,” Krigas said. “People were so hungry to find anything to combat cancer.”

Cisplatin entered human trials in 1972, earned FDA approval six years later and quickly emerged a prominent treatment for testicular, ovarian, bladder, stomach and lung cancers. With testicular cancer, once a death knell for men, cisplatin generated a cure rate north of 90 percent. In 1989, a Rosenberg-led team at MSU earned FDA approval for a cisplatin analogue called carboplatin to treat cancer of the ovaries, head and neck.

Cisplatin delivered a world of good, the effects of which continue flowing today. It ignited the field of cancer therapeutics and fueled new cancer research around the globe, proving the possibilities of intrepid, industrious scientific investigation; it inspired hope and saved millions of lives as a therapeutic workhorse against multiple forms of cancer; and at Michigan State, where Rosenberg worked until his retirement in 1997, cisplatin elevated the university’s profile and expanded the depth and breadth of research across campus.

“Cisplatin’s discovery put Michigan State solidly on the research and academic map for sure,” said Jim Hoeschele (Ph.D., ’69, College of Natural Science) one of Rosenberg’s post-doctoral fellows and a carboplatin co-inventor who would later teach general chemistry and supervise undergraduate researchers at MSU for 15 years.

Nearly six decades after cisplatin’s founding, the anti-cancer drug’s legacy resonates across the MSU landscape. Through the MSU Foundation, some $325 million in cisplatin and carboplatin royalties earned from 1979-2004 have pushed MSU investigators to pursue daring work, fueled enterprising interdisciplinary explorations and propelled countless entrepreneurial adventures.

“Cisplatin wasn’t just a home run,” current MSU Foundation Executive Director David Washburn said. “It was a grand slam.”

Fueling impact

In 1973, then-MSU president Dr. Clifton Wharton created the MSU Foundation, a nonprofit entity designed to support scientific discovery and campus research. Initially tasked to oversee fundraising and trust-related functions as well as various patents companies had donated to the university, the Foundation also doled out modest research grants.

But as the royalties for cisplatin and carboplatin mounted throughout the 1990s, MSU leadership removed fundraising from the Foundation’s charge. The move empowered the Foundation to double down on fostering a more ambitious research environment and stimulating a more robust entrepreneurial culture at MSU. The Foundation created new grant programs while diving deeper into technology transfer, commercialization, early-stage financing and placemaking, a move punctuated by the 113-acre University Health Park that sits on the southwest corner of the MSU campus. It will soon to be home for the new McLaren Greater Lansing Hospital.

In addition to helping build the partnership with McLaren, the Foundation also played a role in helping TechSmith, a global software company, select Spartan Village as the site for their new corporate headquarters. “Both projects bring industry leaders to our campus, which will not only strengthen our current partnerships but create new opportunities for learning and innovating,” said Washburn.

Today, the 22-member MSU Foundation team embraces an unrelenting mission to help support MSU’s research engine and entrepreneurial ecosystem.

“We exist to serve MSU,” confirmed Washburn, the Foundation’s executive director since 2014. To date, the MSU Foundation has awarded more than $350 million to the university through grant programs and other initiatives designed to strengthen research, assist in the development of technologies and bolster MSU’s scholarly infrastructure.

Supporting innovation

Beyond grants, the MSU Foundation plays a prominent role in venture creation and venture investment, successfully transforming cutting-edge ideas into viable organizations through ongoing support that includes programming, capital, physical spaces and collaborative community.

Through its wholly-owned subsidiary company, Spartan Innovations, the Foundation identifies compelling intellectual property from MSU researchers that can serve as the basis for a startup. The Foundation helps promising ventures develop a business plan and construct a foundation for sustainable operations. Through its Red Cedar Ventures and Michigan Rise, two of the Foundation’s venture capital funds, the nonprofit then provides gap and pre-seed funding to propel business development, such as purchasing equipment, hiring staff or attending a trade show.

Finally, the Foundation owns and manages a number of spaces, which includes the 22,000-square-foot VanCamp Incubator and Research Labs named in honor of the conscientious cisplatin co-discoverer as well as the East Lansing Technology Innovation Center on East Grand River Avenue across the street from campus. Providing startups with flexible lease terms, shared services and other resources, the Foundation minimizes many of the traditional challenges that derail startups.

“This way, startups are staying in the East Lansing area and contributing to our local culture and economic fabric,” Washburn said.

Though the research projects and entrepreneurial endeavors the MSU Foundation supports possess inherent risk, Washburn said the university can afford to pursue such bold projects because of the pioneering efforts of Rosenberg and his team.

“Given the size of our endowment because of cisplatin, we can take chances on exploring high-risk ideas,” Washburn said. “We can focus on execution and helping to advance compelling research along that can strengthen MSU and our greater community.”

It is cisplatin’s noble and ongoing legacy—one generation of intrepid minds opening doors and transforming lives for another.

“Who knew we were going to change so many lives in so many different ways?” Krigas said this past summer while sitting in his suburban Chicago home.

Serendipity, indeed.