Time is a funny thing. At the very moment we experience an event, an entire spectrum of human events is unfolding across the globe, involving the world’s other 7.5 billion people. And I find it particularly fascinating when some of those seemingly unrelated events collide.

Hear more from Judith in the podcast episode below:

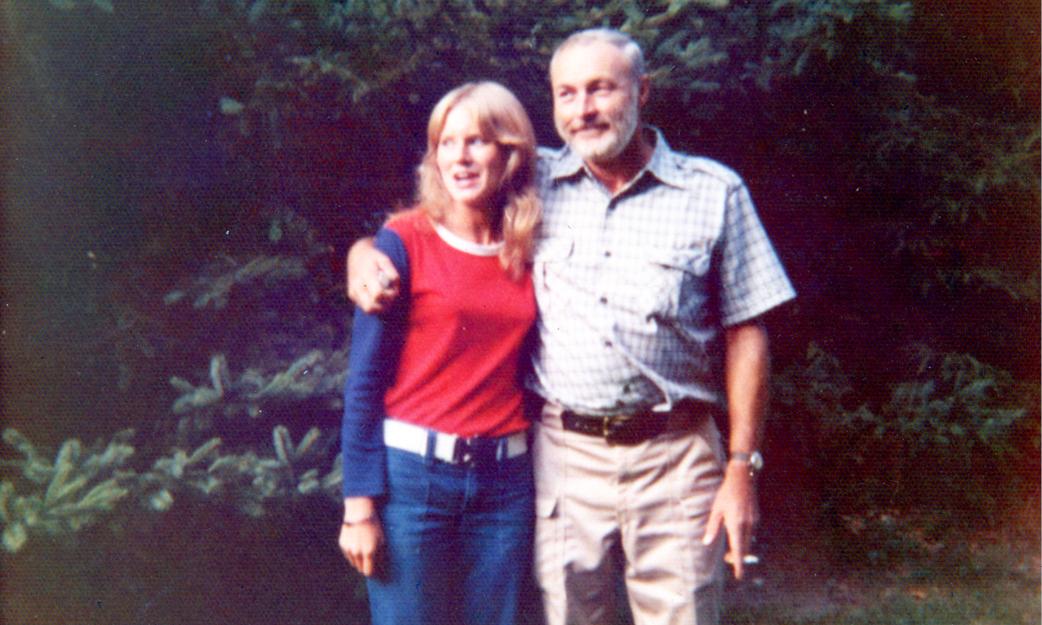

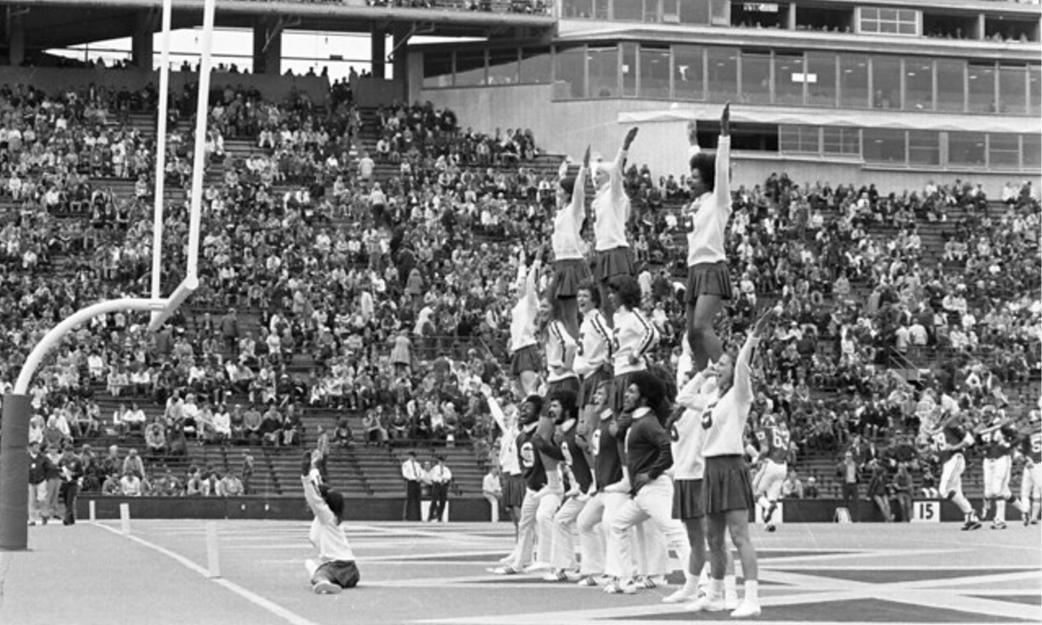

When Dr. Rosenberg discovered what would come to be called cisplatin, I was in seventh grade. It didn’t matter that high school graduation was six years off; my university destination had been pre-determined. My father (Edwin Foster, ’50, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources) had made it clear that my brother (Chip Foster, ’82, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources) and I could go to any college in the city of East Lansing. It sounds cute, but he wasn’t kidding. Thus, when September 1971 rolled around, I officially became a Spartan.

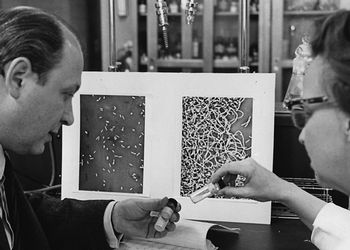

As I was settling into 313 W. Butterfield Hall, the grim survival rate for those diagnosed with cancer was less than 50%. Treatment options were few. But research in anti-cancer drugs (later called chemotherapy) was on the rise, as was combining those drugs into a powerful cancer-killing cocktail. Cisplatin would become “the backbone of combination chemotherapy.” In addition, cancer research was about to be accelerated by the National Cancer Act.

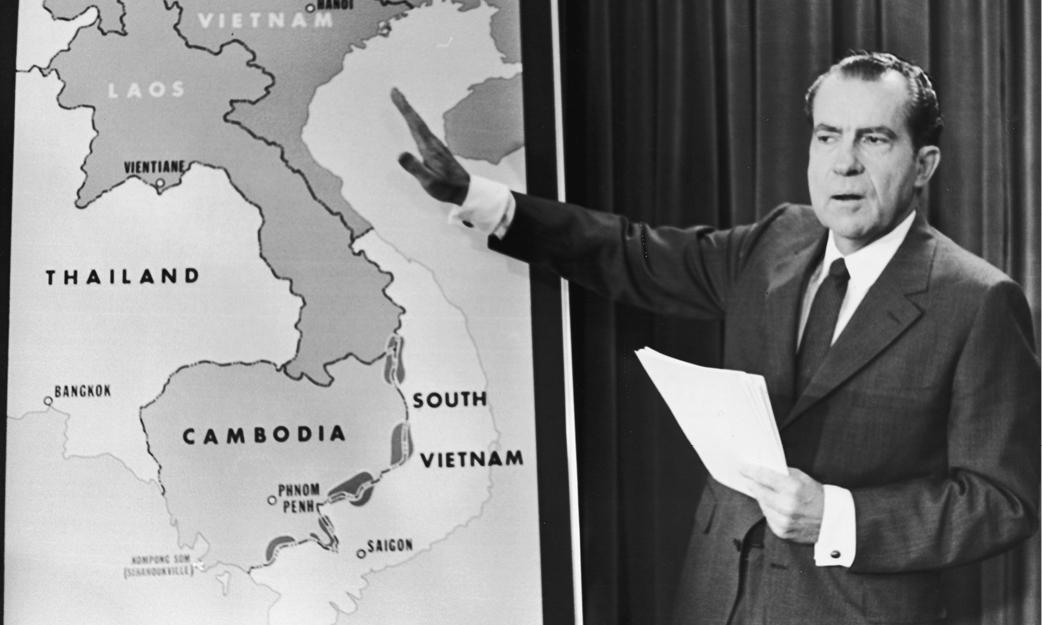

A year before I arrived on campus, beleaguered President Richard Nixon’s approval rating was as grim as the cancer statistics. He had won the 1968 election by promising a “secret” plan to end the war in Southeast Asia. But no plan had materialized. Over on Capitol Hill, however, a heated discussion about national health had become a full-blown fire. And Nixon’s advisers seized upon it. The president could officially declare war on cancer by increasing research funding. Someone even suggested the disease would be cured by the nation’s 1976 bicentennial. It was a win-win for patients and the president alike. Taking on cancer with such bravado could (and did) return Nixon to the White House for a second term. It was a fight behind which everyone—Republicans and Democrats—could rally.

So while I was enjoying Christmas break amid family and friends, Nixon’s war on cancer officially began when he signed the act on December 23, 1971. It promised an unprecedented $1.6 billion ($8.3 billion today) over three years for cancer research. Perfect timing for cisplatin, which went into human clinical trials in 1972 (the year I officially became a French major). I graduated in 1975, and when the bicentennial celebration arrived the next year, Nixon had resigned in disgrace, and cancer was still killing.